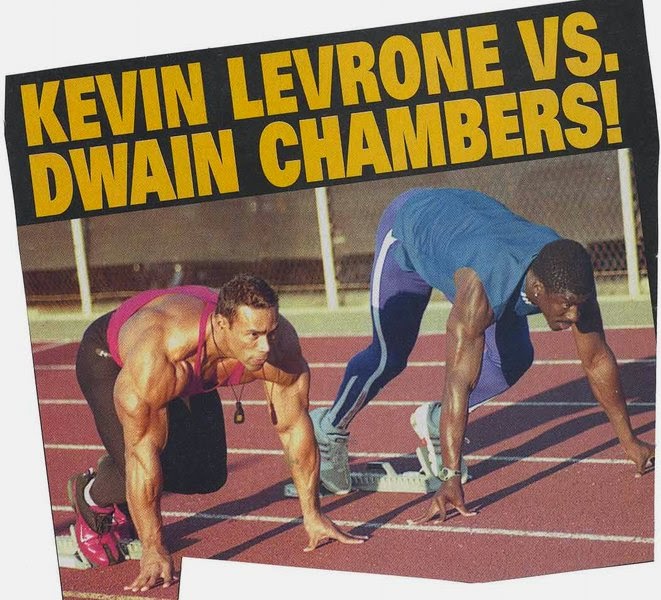

Before a certain Usain Bolt came around, if you asked the regular fitness enthusiast how they would build the ideal sprinter, I'm fairly confident not many descriptions would omit the term 'muscular'. The likes of Linford Christie, Maurice Greene and Ato Boldon all had the chiselled physique of a fitness model. In the early part of this century, Kevin Levrone, a body builder, challenged Dwain Chambers (who at the time could be mistaken for a body builder) to a sixty metre sprint, seemingly convinced he could turn over a world class sprinter. With all of this in mind, you could be forgiven for believing that sprinting is a strength endeavour. The logic being, the faster athletes tend to have more muscle, and therefore tend to be stronger. I believe it is correct that all else being equal, the stronger sprinter will win. But that 'all else' is very important.

I used to be of the over simplistic opinion that if F=ma (force = mass x acceleration), then provided I increased F and m remained fairly constant, a would increase. Each step would deliver more force, and I would run more quickly. Newton seemed like he knew his stuff, so follow his rules and you won't go too far wrong. A lot of elite sprinters looked pretty big, they could apply a lot force, so I would try and do the same. This, however, didn't account for the likes of Carl Lewis, Christian Malcolm and Frank Fredericks, all of whom were far more slender in their build.

I recently read Daniel Coyle's 'The Talent Code', in which he discusses the 10,000 hour rule, which states that in order to reach expert status, 10,000 hours of practise is required, and applies it to various activities. I don't believe this rule is appropriate for sprinting, and agree with Craig Pickering in his article

'Sprinting and the 10,000-Hour Rule'. If Usain Bolt and I both had 10,000 hours of practise, it still wouldn't be a nail-biting contest. However Coyle certainly offered me a new perspective in terms of how I viewed sprinting. I enjoyed the first part of 'The Talent Code' the most, in which Coyle discusses myelin, the sheath which insulates our neurons, allowing the signals to travel more rapidly. In it's wisdom the body detects the frequently used neural pathways, and insulates them with more and more myelin. The more you do a particular movement, the more myelin that gets synthesised around the relevant neurons, the faster and more accurately you can complete that movement. I now understood a mechanism behind skill acquisition and how 'practise' worked! This was great news for me, because unless I understand how and why something works, then I remain pretty cynical.

|

| The myeline sheath coats the nerve. |

Now I understood more about the 'all else', I felt more comfortable prioritising it. I saw more value in drills focussing on the key technical pointers, largely based around posture and foot position, with various other cues depending upon which race aspect is being trained. I also had an explanation as to why it may be beneficial to complete a higher volume of slightly lower intensity work, within reason. Pietro Mennea supposedly completed sessions such as three sets of five reps of 80 metres, followed by three reps of 100 metres, followed by three reps of 400 metres! This session is reported as being completed with two minutes recovery between the reps and nine minutes between the sets. Besides the volume of work being done, what struck me was that these runs would be completed at a significantly sub maximal speed (around 9 seconds for 80 metres and 11.5 seconds for 100 metres, for a 19.72 200 metre guy). In an interview, Hakan Andersson has been quoted as saying that completing 60 to 80 metres at 92-98% intensity allows impressive volumes to be completed with a technique that resembles maximal velocity 'pretty much without fatigue'. When you consider the myelination that could occur in such sessions, provided they are completed with competent technique, it is clear to see how the athlete could benefit. The neural pathways used become better insulated, and therefore movements become more automatic and can be completed more quickly.

|

| Warren Weir demonstrating some well practised mechanics. |

Often we see athletes produce performances indoors over 60 metres that seem superior to what they then produce outdoors over 100 metres (not to say the opposite is not also noticed). This could be due to a number of reasons, but two are relevant to this post. If a programme has an excessive focus on strength development and an inadequate focus on sprinting 'skill', this could lead to two reasons why an athlete may have a better relative 60 metre performance than 100 metre performance. Maximal strength plays a large role in the acceleration segment of a race, which contributes to a greater percentage of a 60 metre performance than it does to 100 metres. Secondly, in the 100 metres speed endurance comes into play. If the sprinters are less skilled, their movements may be less efficient, which could lead to a greater rate of deceleration.

I continue to value the importance of strength work for force application and injury prevention. But if you are able to apply all the force in the world, how helpful is that if it is done so in the wrong direction? Correct movement should be paramount and it needs to be rehearsed to make it more efficient and sharper. When you train are you making myelin work for you?

References:

Interview with Hakan Andersson

http://complementarytraining.net/interview-with-hakan-andersson/

Pietro Menna's Detailed Training Workouts for 200 metres

http://speedendurance.com/2010/05/10/pietro-menneas-detailed-training-workouts-for-200-meters/